Healing as a whole person: what dynamics move us towards wellbeing?

Written by Johanna Lynch – University of Queensland

Well, as I start my final Writer in Residence essay for the ALIVE National Centre for Mental Health Research Translation, I reflect on the privilege of writing, as I set out to do, on the “interconnected wonderfulness of being a whole person”. 1 I have chosen to use each of these essays to address an aspect of being whole. We have reflected together on sensing our inner and outer worlds as whole people1; feeling emotion in our bodies, minds, and communities2; how our biology is impacted by our life story and how sensing we belong can ease the deep embodied experience of shame3; how comforting and healing impact the whole person4; how holistically we defend ourselves against threat5; and how our community impacts our personal sense of capacity to engage with our world6. I have invited readers to see the interconnected embodied whole; to critique current understanding of mood as disorder; to see social determinants of health in a new light; to consider the biology of belonging; to consider the links between wholeness and healing; to resist ignoring the invisible causes of suffering; to be fascinated about what helps us engage with our world; and finally in this essay, to see healing orientation as the new normal.

In this last essay I will be focussing on healing as a whole person dynamic – a movement towards wellbeing that all of us need – practitioners, patients, clients, students, leaders, researchers, and anyone with a lived experience of distress. I will argue for policy and practice that orient towards healing and point towards the importance of caring for the heart of each healing practitioner.

If I could leave one lasting impression from this series – it would be that healing requires movement. Without movement we are stuck. Healing requires a way of seeing that does not diagnose people, personalities, families, or communities with fixed nouns, denotations,7 classifications,8 or deterministic labelling 9 – but rather is tuned into the interconnected verbs that move us forward to engage with life. For those who are carers and leaders – this is a movement towards ‘therapeutic action’.7p.419 Healing is always about movement.

So – let’s start with some definitions of healing. Looking up the history of the word ‘heal’ – we find the verb Hǣlan which is Old English for ‘to heal, cure, save, greet, salute’. We also find the Proto-Germanic word Hailijaną that means ‘to heal, make whole, save’ and the Proto-Indo-European word Koil that means ‘safe, unharmed’. 10 Deep truths can be found within language and its development. Healing is also described in modern dictionaries as a verb – ‘to make free from injury or disease; to make sound or whole; to make well again; to restore to health; to patch up or correct (a breach or division); to restore to original purity or integrity; to become free from injury or disease; to return to a sound state.’ As we seek to learn how to counter the stretching apart that is distress – I think it is important to see the links between wholeness, safety, and the active verbs that move us towards healing.11

Interestingly, at the end of my PhD exploring sense of safety as a whole person approach to wellbeing, I discovered that the word safety came from a Proto-European word that means whole: Solwos. As well as reminders of the interconnected whole, I hope these series of essays remind us all of the importance to human beings of the interconnected active presence of sensing we are safe. My doctoral work has become the ‘Sense of Safety Theoretical Framework’ which highlights the importance of the verbs ‘to save’, ‘to build safety’ and ‘to make whole’ in our understanding of healing.11,12

Healing also has embedded within it an assumption of change – an acceptance of need to adapt to imperfection, challenge, and adjusting relationships, unlike cure which often focusses on resisting change and surviving as we have always seen ourselves.13 This is a mindset shift for healthcare. It involves messy changing verbs rather than certain output nouns.11 It is a subjective internal meaning-making process that is difficult to define. Lets consider together the ways that highly valuing verbs can make healing-orientation usual care in our community!

First Nations academic Emeritus Professor Judy Atkinson defines healing in community in stages that include: awakening to unmet needs; experiencing safety; community support; deepening self-knowledge; meaning-making story in ceremony; personal cultural/spiritual identity; transformation and transcendence; and integration.14 The first steps in her definition are poignant. They remind us that some communities and individuals have experienced so much oppression and injustice that they are often unaware of what healing could be like, or what needs could be met. Her definition is also full of communal and spiritual connections reminding us of the important interconnected impact of healing movement within all communities. This First Nations wisdom can teach us so much.

General practitioners who work on the frontline of our community, can also add to our understanding of what healing is. I recently asked a group of Australian General Practitioners from the Australian Society for Psychological Medicine to write down what they thought healing was. Here are some of their anonymous answers, shared with consent:

Figure 1: Anonymous quotes from Australian family doctors when asked to define healing Australian Society for Psychological Medicine Annual Conference 2024.

Figure 2: More anonymous quotes from Australian family doctors when asked to define healing at the Australian Society for Psychological Medicine Annual Conference 2024

What do you think of these answers?

I am struck by how relational and human they are, and how many verbs are embedded in these descriptions.

General practitioner researchers also describe the healing purpose of their work in these active phrases: “rehabilitate a person’s sense of self”15p.6; “avoid diagnoses that imply a layer of dismissal”16p.104; and “restore or improve the individual’s health related capacity for living”.17p.390 In my very first published paper entitled ‘Beyond symptoms: defining primary care mental health clinical assessment priorities, content, and process’, I wrote about how priorities of primary care focus on building strengths to enable coping, and do not align with psychiatric goals of naming diagnoses that often become fixed labels.18

Another paper describing the nature of healing relationships in primary care names healing processes that include ‘valuing’ each person through a connecting presence and nonjudgemental stance; managing power and control in healing relationships through partnering and education in what they called ‘appreciating power’ ; and abiding through not giving up on each person – a “promise to not abandon the patient even if the pills and technology have little left to offer”.19p.315 They also name relational verbs that are part of healing that include to trust (willingness to be vulnerable within healing relationships, feeling cared for, and knowing that promises will be kept), to hope (belief that some positive future beyond present suffering is possible), and being known (sense that the physician knows the patient as a person).

Wise American physician, Ron Epstein also wrote a beautiful paper entitled ‘Responding to suffering’ in which he wrote about ‘turning towards’ (that includes recognising suffering, becoming curious about the patient’s experience, and intentionally becoming more present and engaged) and ‘refocussing and reclaiming’ (enabling patients to connect to what they see as important, meaningful, and generative despite adversity).20 He highlights the skills of listening deeply, and recognising ambiguity, incompleteness, and contradictions. Listening deeply is also an active part of healing that Australian First Nations elder Miriam Rose Ungunmer teaches as a part of First Nations ways of being – ‘Dadirri’ – in the language of the Ngan’gikurungurr and Ngen’gwiumirri peoples.21 The actions and movements of turning towards and listening deeply to people matter. They enable healing.

Movement is also central to the descriptions of healing described by those with a lived experience of mental distress who have recovered. They describe movement from passive to active sense of self, from disconnection towards connection, and hopelessness towards hope.22 Their descriptions of recovery are summarised in the mnemonic ‘CHIME’: Connectedness, Hope, Identity, Meaning, and Empowerment.23 Recovery is active, individual, unique, gradual, non-linear, and multidimensional. It is also a journey of struggle and life-changing trial and error. This movement towards healing is part of ordinary living and is something that can occur without professional intervention.23

Wouldn’t it be great if a focus on this kind of healing was the new normal??

In my doctoral work developing the Sense of Safety Theoretical Framework for whole person care, I analysed the data for verbs and found patterns that could help practitioners, individuals, communities, and workplaces to orient towards healing.11 These processes build sensed safety. They emerged from clinical experience, transdisciplinary literature, and multidisciplinary and lived experience participatory conversations.24 These dynamics are designed to offer an alternative to psychiatric categorising and prescribing. They describe not what is wrong with a person, but what could become their pathway to wellbeing. They are focussed not on ‘what happened?’ but on ‘what next to help you feel safer?’ They are ordinary processes that every person needs in life. In other places I have described these dynamics in more detail11,24-26 – in this essay I will point out their ordinary goodness. These dynamics can be offered by anyone seeking to comfort another person – not just by professionals.

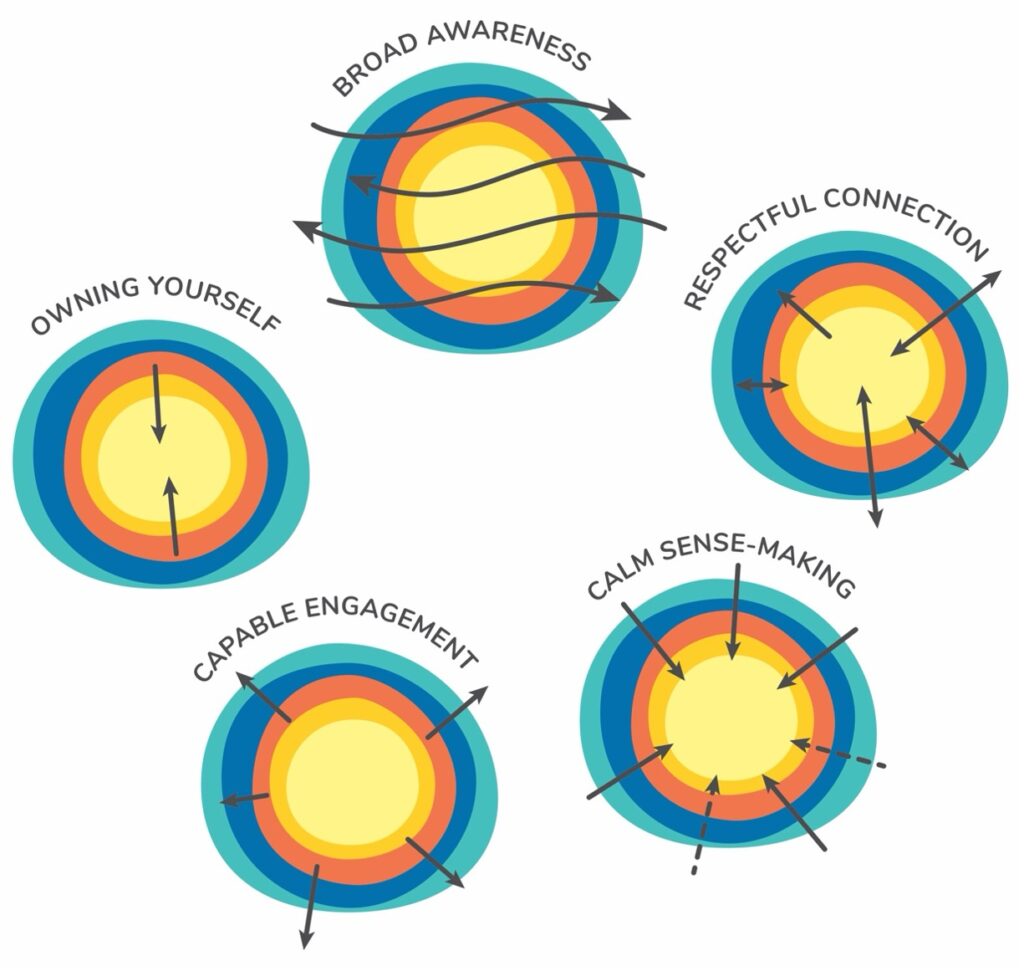

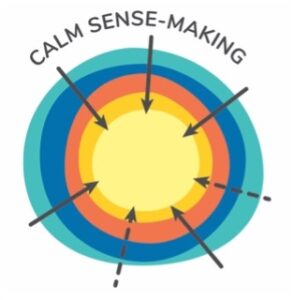

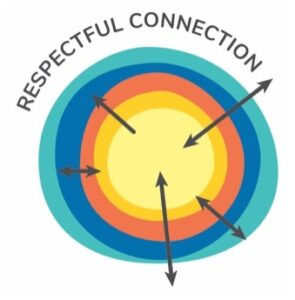

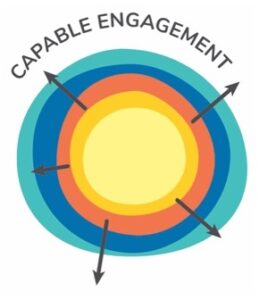

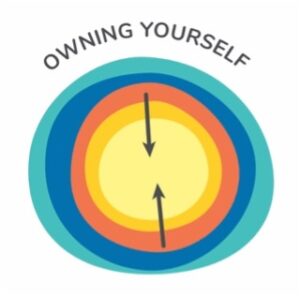

The five Sense of Safety Dynamics that are part of the Sense of Safety Theoretical Framework are Broad Awareness, Calm Sense Making, Respectful Connection, Capable Engagement, and Owning Yourself. These dynamics underpin processes that facilitate the deep human need for safety.27 They are more important than symptom control and diagnostic certainty. They are relevant for every part of a whole person – their environment, social climate, relationships, body, inner experience, sense of self, and spirit/meaning. These Sense of Safety Dynamics are implicit priorities of anyone who is a healer. Naming them makes these implicit skills explicit. In Figure 3, each of these dynamics are depicted as flow across the whole person across self, other and context – including directional arrows that depict the internal movement of attention and action.

Figure 3: Sense of Safety Dynamics. Reproduced with permission Lynch, J.M (2021) A whole person approach to wellbeing: Building sense of safety. Routledge. London

Broad awareness is an active intuitive awareness of multiple aspects of self, other, and context – all at once. It is the experience we have when we go on a bush walk and we are aware of the sounds, the smells, what we are looking forward and who we are with. It is a wide noticing that includes your peripheral vision and sense of what is behind you. It includes an awareness of past, present, and future. It includes a capacity to sense what other people experience. It is the opposite of feeling ‘triggered’, ‘freaked out’, ‘numb’, ‘flooded’, ‘switched off’ or having your attention narrowed by fear. Ordinary words to describe broad awareness are: ‘seeing the big picture’ and ‘being present’.11 This is a neurological and social process that involves attention, reflective capacity, empathy, attunement, resonance, and awareness. It happens when we enjoy a view, connect in a conversation, understand something, take a wide perspective on something or see it from a different point of view. It can be learned and practiced and therapeutic techniques like mindfulness, mentalising and dialectic behaviour therapy can build it. It is involved in humour and music and lying in the grass. It is a whole curious observant way to see ourselves, our community, and our world.

Calm Sense Making is clear headed embodied inner and communal organisation. It occurs within the self through inner reflection, emotion regulation, and body feedback systems that produce calm. It occurs between people in co-regulation, dialogue and storytelling, and within communities through ceremony, rituals, tradition, history keeping, and culture. It occurs between people and the natural and spiritual world in awe, creating, meaning-making, worship, prayer, and scientific enquiry that seeks to understand. It is the opposite of feeling confused, disconnected, disorganised, reactive, fragmented, overwhelmed, and incoherent. It has ordinary words to describe it: ‘gathering ourselves together’, ‘grounded’, ‘insightful’, ‘reflective’, discerning’, ‘wise’, and ‘having it in perspective’.11 This is relational and neurological, it involves making sense of ourselves and our world, it involves insight, revelation, pattern recognition and perspective. It is wide and deep and clear. It is hidden inside routines and predictable rhythms, and in ordinary debriefs after big days. It is in tears and stories and deeply inside culture. Even the process of creating a sentence requires fragmented ideas and feelings to become words and then become orderly grammatical sentences that help us to understand ourselves. It is also in biological calming and self-regulatory feedback cycles. It can be in creating a meal, planning a party, painting, acting, dancing, writing, and singing – where both shapes, colours, movement, lyrics and melody help us to make sense of our world.

Respectful connection is a kind of connection received and given within ourselves, and between us and other people, and our environment. It is attuned, trusting, and respectful. It is the kind of relationship that is in safe attachment relationships and talked about as part of the Duluth Equality Wheel (respect, trust and support, honesty and accountability, responsible parenting, shared responsibility, economic partnership, negotiation and fairness, and non-threatening behaviour).28 And it is in tenderness and gentle tone of voice. It is apologies and repair and reconciliation. It is a giving and receiving of love towards ourselves, and others, and our world. It is the opposite of rejection, loneliness, abandonment, disconnection, being ‘ghosted’, marginalisation, racism, deceit, exploitation, self-hatred, betrayal, disharmony, suicidal ideation, estrangement and so many other painful relational experiences. Ordinary words to describe it are ‘seen’, ‘heard’, ‘valued’, ‘welcomed’, ‘cared for’, ‘supported’, ‘respected’, ‘belonging’, ‘trust’, ‘self-acceptance’, and ‘loved’.11 At the heart of respectful connection are ordinary kindnesses, communal etiquette, heartfelt apologies, and reconciliation..

Capable Engagement is a dynamic movement towards the world. It involves self-expression, growth, and purposeful engagement with self, others, and the wider world. It also involves an environment that offers access, opportunity and encouragement to enable you to have your say and be free to move and grow and learn. It is the opposite of being stuck, out of control, insecure, fragile, trapped, constrained, controlled, manipulated, voiceless, or passive. Ordinary words for this dynamic include being curious, creative, confident, and able. It includes being able to influence, negotiate, take appropriate risks, move, express, advocate, and be effective.11 The two sides of building capable engagement include being in a community that helps you to give it a go and being willing to try something new.

Owning yourself is a journey towards feeling comfortable, capable and aligned with your whole self. It includes a physical sense of comfort in your body, and with all parts of who you are. It is also experiencing yourself being acknowledged by others. This theme came from someone with a lived experience of mental illness saying that sense of safety is “owning yourself and your experiences.” It includes a sense of autonomy, self-trust, self-control, inner reflective attention and affection, inner unity, feeling ‘good enough’ and “ok to make mistakes”, feeling ‘in control of my life’, having ‘confidence to be able to cope with adversity’, and having ‘agency to address threat…[and] agency to make your world safer.11 The opposite of this dynamic is disconnection, being exposed, powerless, or intoxicated, overwhelmed by expectations, bullied, feeling stupid, shamed, disowned, inner neglect or attack, and loss of autonomy. Ordinary words for this dynamic are integrity, backing yourself, taking responsibility for yourself, owning up, being boundaried, differentiated, having inner alignment, and self-control.11 Especially in health, this dynamic needs to be taught and retaught – so that both clinician and patient remember to enable a person to be charge of their own pathways forward.

Each of these dynamics are ordinary and they are essential to wellbeing. They bring together movements of attention, affection, and connection between people, self, and the wider world. They involve sensing and sense-making, and they include movement towards tuning in, understanding, respecting, engaging, and owning. They are neurological, relational, meaningful, and contextual. These dynamics can be guidelines for family life, for classrooms, workrooms, waiting rooms, clinic rooms, and boardrooms. They can be built in small everyday interactions as well as be the underpinning of complex therapeutic techniques. They can guide public policy and private practice. They involve community as well as the inner private life of each person. They are a kind of description of what it is like to be comforted, encouraged and loved. They assume a shared responsibility for building sense of safety as we are all community members and citizens of our own meaningful lives.

I reflect now on three ordinary processes that brought healing for people I have cared for over the years – shared with consent. One was a woman who later thanked me for giving her children back their mother. Her healing came when she reconnected to an early childhood dream to do deep sea kayaking. She saved up and had a kayak made that she could enjoy, then became healthier by catching and eating her own fish and enjoying the outdoor adventures. This was a story of owning herself and growin in capacity for calm sense making about what matters to her. Another was a patient who took on the cooking for her son’s wedding as a way of reengaging with life as mother, away from the trapped experience of her abusive childhood. This was a movement towards capable engagement and respectful connection. Lastly – a patient who started writing poems and music to help her remember who she was and what she had faced and overcome. This was a practical way for her to make sense of her life and increase her own respectful connection towards herself.

In my postdoctoral research, physiotherapists (n=6), Australian, USA, and Norwegian family doctors (n=42), occupational therapists (n=3), domestic violence social workers (n=9), teachers (n=6), mental health clinicians with a lived experience of mental illness (n=3) and a small multidisciplinary rural health team (n=7) were asked to reflect on how they already build sense of safety. Themes that aligned with the Sense of Safety Dynamics emerged and practitioner skills and attitudes, as outlined in Table 1.12

Table 1: Practitioner Skills and Dynamics that facilitate Sense of Safety Dynamics

| Practitioner Skill and Attitude | Sense of Safety Dynamic |

| Valuing the whole picture (includes a generalist gaze, seeing the system, tuning into both bodies, and including paradox) | Broad Awareness |

| Holding Story Safely (includes inviting the story, holding and containing, soothing and co-regulating, joining a dance and integrating wisely) | Calm Sense Making |

| Being with you (includes being comfortable with not knowing, being present, having their back, repairing ruptures, and taking care) | Respectful Connection |

| Learning together (includes holding space for collaboration, rebuilding boundaries together, envisioning and future, seeing safely, and believing in them) | Capable Engagement |

| Protecting dignity (includes welcome and invitation, seeing and protecting the person’s dignity, reminding them of their capacity, and drawing inwards to centre myself too) | Owning Yourself |

As I come to the end of this last essay. Can I also remind all those readers who are healers or carers to care for themselves too. Here are a few quotes chosen to encourage you that your own healing matters.

My favourite quote about this is from Henri Nouwen. His link between hospitality and healing is so helpful – those of us who heal need to feel at home in the free and fearless spaces (that have a sense of safety )that we hold for others to heal:

“What does hospitality as a healing power require? It requires first of all that the host feel at home in their own house, and secondly, that they create a free and fearless place for the unexpected visitor.” 29p.89

Another reminder of our humanity:

“Compassion is not a relationship between the healer and the wounded. It’s a relationship between equals. Only when we know our own darkness well can we be present with the darkness of the other. Compassion becomes real when we recognise our shared humanity.” 30p.235

And a reminder not to take on all the pain of the world – because when we do it can make us helpless and drive overwhelming demands on ourselves:

“the therapist’s defence against feelings of helplessness leads to a stance of grandiose specialness or omnipotence…[leading to] aspirations to heal all, know all, and love all.”31p.143

And finally a reminder to hold the healer’s task lightly – that meaningful life is inspired not given:

“a meaning must be found and cannot be given… Meaning is like laughter… you cannot forces someone to laugh – you must tell him a joke! The same applies to faith, hope, and love – they cannot be brought forth by an act of the will, our own or someone else’s.”32p.112

These series of essays have been a reminder to see the movement across the whole wonderfulness that is part of being a person. These are the verbs we have considered: sensing1, feeling6, experiencing33, comforting4, defending5, connecting3, belonging3, engaging, and healing. Each of these verbs is part of the beautiful journey towards healing. They are vibrant and active and so much more helpful than categorising nouns originally designed for research. They are verbs of wellbeing.11 Seeing them across the whole person could be the new normal for how we see and celebrate healing in our community.

The writer would like to thank Dr Rubayyat Hashmi for their review of an earlier draft.

- Sensing as a whole person: is sensation more than anecdotal evidence? An invitation to see the interconnected embodied whole.

- Feeling as a whole person: are emotions in our bodies or our minds? An invitation to critique current understanding of mood as disorder.

- Connecting as a whole person: what do shame and loneliness have in common? An invitation to consider the biology of belonging.

- Comforting as a whole person: does it matter if we miss a part? An invitation to consider the links between wholeness and healing.

- Defending as a whole person: is violation the only threat we care about? An invitation to resist ignoring invisible causes of suffering.

- Is feeling safe a platform for courage? Building Sense of Safety for whole person wellbeing. An invitation to be fascinated with what builds enough courage to engage with our world.

- Sadler JZ. Values and psychiatric diagnosis. Oxford University Press; 2005.

- Langeland E, Wahl AK, Kristoffersen K, Hanestad BR. Promoting coping: Salutogenesis among people with mental health problems. Issues in Mental Health Nursing. 2007;28(3):275-295.

- Mazzocchi F. Complexity in biology: Exceeding the limits of reductionism and determinism using complexity theory. EMBO reports. 2008;9(1):10-14.

- Murphy ML. The American Heritage® dictionary of the English language. Dictionaries: Journal of the Dictionary Society of North America. 2001;22(1):181-199.

- Lynch JM. A Whole Person Approach to Wellbeing: Building Sense of Safety. Routledge; 2021

- Lynch JM, Stange, K.C., Dowrick, C., Getz, L.O, Meredith, P.J, van Driel, M., Harris, M.G., Tillack, K., Tapp, C. The Sense of Safety Theoretical Framework: a trauma-informed and healing-oriented approach to the whole person. Frontiers in Psychology. 2024;in press

- Hutchinson TA. Whole person care : a new paradigm for the 21st century. Springer; 2011.

- Atkinson J. Trauma Trails: Recreating Songlines. The transgenerational effects of trauma in Indigenous Australia. Spinifex Press; 2002.

- Stone L. Reframing chaos: A qualitative study of GPs managing patients with medically unexplained symptoms. Australian Family Physician. 2013;42(7):1-7.

- Stone L. Making sense of medically unexplained symptoms in general practice: a grounded theory study. Mental health in family medicine. 2013;10(2):101-111.

- Reeve J. Scholarship-based medicine: teaching tomorrow’s generalists why it’s time to retire EBM. Br J Gen Pract. 2018;68(673):390-391.

- Lynch JM, Askew DA, Mitchell GK, Hegarty KL. Beyond symptoms: Defining primary care mental health clinical assessment priorities, content and process. Social Science & Medicine. 2012;74(2):143-9. doi:10.1016/j.socscimed.2011.08.043

- Scott JG, Cohen, D., DiCicco Bloom, B., Miller, W., Stange, K., Crabtree, B. Understanding healing relationships in primary care. Annals of Family Medicine. 2008;6(4):315-322.

- Epstein RM, Back AL. Responding to suffering. JAMA. 2015;314(24):2623-2624.

- Ungunmerr MR, ed. Dadirri: Listening to One Another. Aboriginal and Torres Strait Islander Apostate, Catholic Archdiocese of Brisbane; 1993. Hendricks J, Heffernan G, eds. A Spirituality of Catholic Aborigines and the Struggle for Justice.

- King R, Lloyd C, Meehan T, eds. Handbook of Psychosocial Rehabilitation. Blackwell Publishing; 2007.

- Leamy M, Bird V, Le Boutillier C, Williams J, Slade M. Conceptual framework for personal recovery in mental health: systematic review and narrative synthesis. The British journal of psychiatry. 2011;199(6):445-452.

- Lynch JM. Sense of Safety: a whole person approach to distress. University of Queensland; 2019.

- Lynch JM, Thomas HR, Askew DA, Sturman N. Holding the complex whole: Generalist philosophy, priorities and practice that facilitate whole-person care. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2023;52(7):428-433.

- Sense of Safety for Practitioners Foundation Course. Lynch JM. 2024.

- Maslow AH. Motivation and Personality Third Edition. Harper Collins Publishers; 1954.

- Pence E, Paymar M. Education groups for men who batter: The Duluth model. Springer Publishing Company; 1993.

- Nouwen HJ. The wounded healer: Ministry in contemporary society. Image; 1979.

- Brown B. Daring greatly: How the courage to be vulnerable transforms the way we live, love, parent, and lead. Penguin Random House UK; 2012.

- Herman JL. Trauma and Recovery: from domestic abuse to political terror. Pandora HarpersCollins Publishers Inc; 1992.

- Frankl VE. The Unconscious God: Psychotherapy and Theology. Simon and Schuster; 1975.

- Experiencing as a whole person: how does lived experience impact biology? An invitation to see social determinants of health in a new light.

About the writer

Dr Johanna Lynch MBBS PhD FRACGP FASPM Grad Cert (Grief and Loss) is a retired GP who writes, researches, teaches, mentors and advocates for generalist and transdisciplinary approaches to distress that value complex whole person care and build sense of safety. She is an Immediate Past President and Advisor to the Australian Society for Psychological Medicine and is a Senior Lecturer with The University of Queensland’s General Practice Clinical Unit. She spent the last 15 years of her 25 year career as a GP caring for adults who are survivors of childhood trauma and neglect. She consults to a national pilot supporting primary care to respond to domestic violence.