Sensing as a whole person: is sensation more than anecdotal evidence?

Written by Johanna Lynch – University of Queensland

As I write the first of a series of articles for the ALIVE Writer-in-Residence program I am wrestling with where to start and how to talk in a series of separate articles about the interconnected wonderfulness of being a whole complex person. My solution is to plan a series that reflects on the interconnections of facets of being whole. Over this set of essays, we will reflect together on being whole people who sense, feel, experience, connect, comfort, defend, encourage, and heal. These themes are intentionally verbs, not nouns. They describe active processes that we can all be part of for our own wholeness and to help us see the wholeness of others.

As some of you may know, I am an Australian General Practitioner (GP) who became a GP psychotherapist so I could care for people that the mental health services in my community dismissed, ignored, or pathologised. I have become fascinated and passionate about making sure that whole person care becomes normal care in health, education, and the social services sector. This has led me on a journey of learning about trauma, grief, attachment, and the biology of stress (and so much more across the disciplines). At one point (2009- 2013) it led me to create a transdisciplinary clinic called Integrate Place that offered generalist care, art therapy, trauma-informed yoga, mental health nursing, and attachment based social work care to adults who had survived trauma and neglect in their community.

This passion for whole person care also led me to research. It led me to reflect on the philosophy of how we know about people and how people change and grow. It also made me search for shared language and goals that might unify how the disciplines see and care for whole complex people This search led me to see how biotechnical approaches that highly value precision and prediction have an inbuilt narrowed gaze that blinds them to the rich complexity of how culture, relationships, meaning and context impact health. It also made me fall back in love with generalism – a way of seeing, listening, questioning, discerning, and caring that integrates both the biography and biology of each person as part of a complex whole. 1p.5,2-5

In this series of essays, we will reflect on ways of seeing and being and knowing that help us to see whole people. We will start with the verb sensing. What do you think of when you think of the word sensing?

For me as a clinician indoctrinated in the value of a certain kind of ‘evidence’, the word sensing used to imply something unreliable, not precise or predictive enough to be useful for medical decision making, and perhaps the worst accusation: ‘anecdotal’ which was code for ‘unscientific’. This suspicion was applied to both the patient’s sensations and the clinician’s own invisible internal praxis wisdom and intuition. Sensing was often described in medical settings as ‘subjective’ – a kind of dismissive reductionist code for ‘not objective’ or even ‘not real’. We sometimes see this in descriptions of symptoms as ‘psychological’ or the slightly less offensive ‘functional’ (implying subjective, internal, invisible but impacting someone’s capacity to function) compared to ‘organic’ (implying observable, objective, or real to the clinician). But is it reliable and scientific to only value as ‘real’ what can be observed from outside?

Meanwhile, over the years, I have been learning from the brave honesty of the people I cared for as they described their life stories, inner experiences, memories, yearning, pains, and joys. Their insightful and reasoned reflections on their lived experience have changed me. Miranda Fricker says it is unjust to not value knowledge from inside the knower.6 Inner subjective knowledge requires different ways of understanding that are not focussed on precision and prediction. To see internal processes, we need to value knowledge that is experiential, authentic, culturally grounded, meaning making, and created with other people in relationship. This way of knowing adds so much to how we understand the world.

In a world obsessed by ‘science’ as ‘reality’, it is perhaps important to notice that subjective information is also ‘scientific’ – if we agree with Iain McGilchrist’s definition of science as: “neither more nor less than patient detailed attention to the world”. 7p.5 Sensing is not just ‘anecdote’; it is a complex experiential way of knowing.

It is also important to critique the archaic assumptions of those who overvalue objectivity and assume that the body is an object that is ‘completely explorable’.8p.2 Assumptions that the disembodied observer’s (‘objective’) mind is more reasonable and reliable than their own subjective experience (or that of the person they are caring for) are not aligned with the current science of a complex interconnected person.9

This brings us back to sensing. I have become completely fascinated by how sensing is an interconnected continuous oscillatory feedback process between inner and outer knowing.10,11 Sensing is not just a simple linear process of perceiving, thinking and acting. For example, the sensors in the microbiome unconsciously influence mood, and past experience can alter our perception. Each time we sense something in our inner or outer worlds, our conscious and unconscious awareness links to our life story, beliefs, reasoning, and intuition as we ‘make-sense’ of the world.

Sensing is so complex and interconnected that it completely blows apart any artificial distinctions between objective and subjective, body and mind, inner and outer, and even past and present.

I have come to love sensation as a kind of moment-by-moment way of knowing about the world that integrates and connects the whole, and is owned by the knower. Only they can know what they sense, it cannot be defined from outside. Sensing and sense-making are so intertwined.12,13 Sensing is a kind of unity, a perception of the whole, not just a bodily reaction to environment.

Along with new understanding of the multilayered whole person, there is a growing literature that explores the role of a part of the brain called the insula. The insula organises, connects,14 interprets14,15 and integrates sensation, perception, emotion, thoughts and plans. Florian Kurth says this creates “one subjective image of ‘our world’.”16p.519 Although this image is not always accurate, or complete, or conscious, it matters.

Interestingly, when people are asked to rate their own health, their sense is more accurate than medical assessments of their wellbeing. Marja Jylha calls self-rated health a “cross-road between the social world and psychological experiences on the one hand and the biological world on the other.”17p.308 This cross-road is where those who offer whole person care need to sit, listen, learn, and care. Respect for sensing could help us all, in Bradley Lewis’s words, to develop “better, truer, richer, and more generous stories … in the service of healing and coping.18p.196

Sensation is also responsive to small changes, tuned in to relationships, context, inner values and history. Our cells sense danger, and temperature change and oxygen levels (and so much more!). We sense ourselves in relationship to gravity and movement (proprioception), and the circadian rhythms of the sun. We even sense what is behind us. We use our senses to relate to others – to tune into their facial expressions and tone of voice (known as prosody). When we are fearful, we find it harder to hear the human voice as our ear drum changes to hear low sounds. We sense our emotions, and we sense threat (what Stephen Porges has called ‘neuroception’19), and we sense our capacity to cope. We sense when we belong, and whether we have existential or spiritual peace or despair. We even sense our relationship to place (connection to country) and to the future (sense of hope).

As you are reading this – I am wondering if you could reflect on your current ‘sense of’ yourself? Where are you and who is nearby? How do you sense yourself and your spirit? When you tune into it are you aware of interconnections and how you know about your whole person?

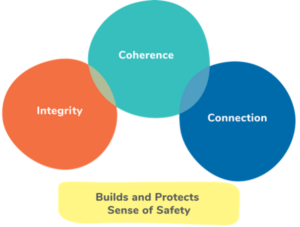

When all these layers of sensation work seamlessly together, they often go unnoticed, and yet they have a purpose: to help us to enjoy and be safe in our world. In my doctoral research exploring threat and sense of safety,3 it emerged that sensation protects our:

- Integrity – both physical and moral

- Coherence – that the world makes sense –

- Connection – to other people

Figure 1: What senses protect: From the cellular to the communal

(Used with permission Figure 5.1 Lynch, J.M. (2021) A whole person

approach to wellbeing: Sense of safety. Routledge: UK (p.78)

In complex systems, reality is probed, sensed and responded to.20 So if we want to know about complex whole people, we need to value and respect sensation. We also need to understand its limitations, the way it can be numbed, or dissociated, or hyperaware and hypervigilant, or distorted, altered, and confusing.

Awareness of sensation and sense-making can transform clinical practice. In my work with adult survivors of childhood maltreatment, I had to learn to be very aware of sensation – my own and those of the person I was caring for. Sensation became a friend as it prioritised the voice of the person who was sensing, and reduced the focus on what Paul Verhaeghe critiques as the ‘ascendant medical observer’.21 Sensing was also a gift through grounding techniques, attuned therapeutic connection, and learning to trust my own intuitions. It became a guide when trying to understand something embodied that had no words in assessment and in my own selfcare. It also helped me to make sense of coping mechanisms: how disconnection, numbness, distraction (for example using obsessions and addictions), or creative flow and activity helped people to alter their sensations to a dose they could tolerate.

Sensing became a way to understand whole people. Rather than being dismissed as anecdotal evidence, it is now central to both assessment and treatment. Sensing can help both people in the therapeutic relationship to tune into their own needs. Highlighting a person’s ‘sense of…’ is an amazing combination of subjective and objective knowing that normalises caring for the many layers of being a whole person. Understanding the beautiful complexity of sensing could transform care.

The author would like to thank Rebecca Moran for helpful comments on an earlier draft.

- Lynch JM, Kirkengen AL. Biology and Experience intertwined: trauma, neglect and physical health. In: Benjamin R, Haliburn J, King S, eds. Humanising Mental Health Care in Australia: A Guide to Trauma-informed Approaches. CRC Press Taylor and Francis Group, Routledge; 2019:195-207.

- Lynch JM, Dowrick CF, Meredith P, McGregor SLT, Van Driel M. Transdisciplinary Generalism: naming the epistemology and philosophy of the generalist. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2020;27(3):638-47. doi:http://doi.org/10.1111/jep.13446

- Lynch JM. A Whole Person Approach to Wellbeing: Building Sense of Safety. Routledge; 2021

- Lynch JM, van Driel M, Meredith P, et al. The Craft of Generalism: clinical skills and attitudes for whole person care. Journal of evaluation in clinical practice. 2021;

- Lynch JM, Thomas HR, Askew DA, Sturman N. Holding the complex whole: Generalist philosophy, priorities and practice that facilitate whole-person care. Australian Journal of General Practice. 2023;52(7):428-433.

- Fricker M. Epistemic injustice: Power and the ethics of knowing. Oxford University Press; 2007.

- McGilchrist I. The master and his emissary: The divided brain and the making of the Western world. Yale University Press; 2019.

- Kirkengen AL, Lygre H. Exploring the relationship between childhood adversity and oral health: An anecdotal approach and integrative view. Medical Hypotheses. 2015;85(2):134-140.

- Barnacle R. Phenomenology and wonder. In: Barnacle R, ed. Phenomenology. RMIT Publishing; 2001:3.

- Koziol LF, Budding DE, Chidekel D. Sensory integration, sensory processing, and sensory modulation disorders: Putative functional neuroanatomic underpinnings. The Cerebellum. 2011;10(4):770-792.

- Engel AK, Fries P, Singer W. Dynamic predictions: oscillations and synchrony in top–down processing. Nature Reviews Neuroscience. 2001;2(10):704-716.

- Marks LE. The unity of the senses: Interrelations among the modalities. Cognition and Perception. Academic Press; 2014.

- Laird JD, Lacasse K. Bodily influences on emotional feelings: Accumulating evidence and extensions of William James’s theory of emotion. Emotion Review. 2014;6(1):27-34.

- Simmons WK, Avery JA, Barcalow JC, Bodurka J, Drevets WC, Bellgowan P. Keeping the body in mind: insula functional organization and functional connectivity integrate interoceptive, exteroceptive, and emotional awareness. Human brain mapping. 2013;34(11):2944-2958.

- Nguyen VT, Breakspear M, Hu X, Guo CC. The integration of the internal and external milieu in the insula during dynamic emotional experiences. Neuroimage. 2016;124:455-463.

- Kurth F, Zilles K, Fox PT, Laird AR, Eickhoff SB. A link between the systems: functional differentiation and integration within the human insula revealed by meta-analysis. Brain Structure and Function. 2010;214(5-6):519-534.

- Jylhä M. What is self-rated health and why does it predict mortality? Towards a unified conceptual model. Social science & medicine. 2009;69(3):307-316.

- Lewis B. The four Ps, narrative psychiatry, and the story of George Engel. Philosophy, Psychiatry, & Psychology. 2014;21(3):195-197.

- Porges SW. Neuroception: A subconscious system for detecting threats and safety. Zero to Three (J). 2004;24(5):19-24.

- Kurtz CF, Snowden DJ. The new dynamics of strategy: Sense-making in a complex and complicated world. IBM systems journal. 2003;42(3):462-483.

- Verhaeghe P, ed. On Being Normal and Other Disorders: A Manual for Clinical Psychodiagnostics. Other Press,; 2004.

About the writer

Dr Johanna Lynch MBBS PhD FRACGP FASPM Grad Cert (Grief and Loss) is a retired GP who writes, researches, teaches, mentors and advocates for generalist and transdisciplinary approaches to distress that value complex whole person care and build sense of safety. She is an Immediate Past President and Advisor to the Australian Society for Psychological Medicine and is a Senior Lecturer with The University of Queensland’s General Practice Clinical Unit. She spent the last 15 years of her 25 year career as a GP caring for adults who are survivors of childhood trauma and neglect. She consults to a national pilot supporting primary care to respond to domestic violence.